The nearest market in Purcine, a mountain village in the southwest of Haiti, is a four-hour walk from the town. People go there on mules to sell the produce of their farms (mainly beans, since Hurricane Matthew destroyed the coffee plantations). And yet, “the area of Jérémie is a safe haven”, a free zone outside the guerrilla war between the gangs that are destroying Haiti. Father Massimo Miraglio, a Camillian priest who has lived in this stateless country for 18 years, one of the few Italian missionaries left in this Caribbean hellhole, spoke to SIR about it.

UN peacekeepers due to arrive soon. A few days after the adoption of UN Resolution 2699, which authorises a multinational security mission led by Kenya to ‘protect’ Haiti, the Italian missionaries are breathing a sigh of relief. But they are not letting their guard down. They know that even UN missions can fail, as happened in 2004 with the Brazilian-led contingent, which was there for 13 years before being forced to recognise its ineffectiveness. “Armed gangs are everywhere, but they don’t reach us up here. It only happened once, but it was men who had grown up here in Jérémie and knew the area well. Here, in the Purcine mountains, we are protected from guerrilla warfare because there is no way to get here except by mule,” Father Maximus explains over the phone. The internet connection is flickering and operates on time slots: communication with the rest of the world is virtually non-existent.

There is no electricity in Jeremie, no water in the village. There is no hospital. People go about their business in the dark, drinking and washing themselves by collecting rainwater.

But in this oasis of beauty and precariousness, destroyed previously by the brutal force of Hurricane Matthew, at least there is no war. “Ours is a small mountain village and that is our good fortune,” says the Camillian Father.

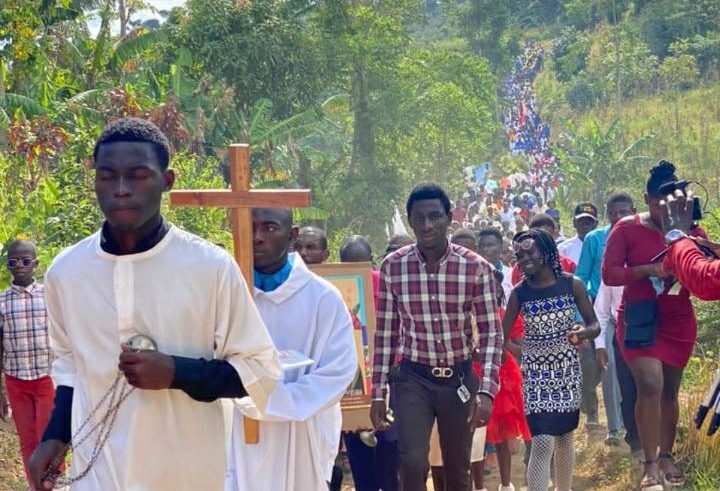

Another hurricane would wipe out everything. The Creole community is resilient, says the missionary, and “the local population has recovered from the climatic devastation, but their houses are vulnerable, and if another hurricane hit, no one would be left alive, not even me.” Last year, Father Massimo had asked to gain experience in Jeremie, in a parish with at least one chapel, and he found it. “I have been parish priest here since the 4th of August,” he says, “in the church of Our Lady of Perpetual Help. For the first time since its foundation, this community of 4,000 people has a priest.”

Another hurricane would wipe out everything. The Creole community is resilient, says the missionary, and “the local population has recovered from the climatic devastation, but their houses are vulnerable, and if another hurricane hit, no one would be left alive, not even me.” Last year, Father Massimo had asked to gain experience in Jeremie, in a parish with at least one chapel, and he found it. “I have been parish priest here since the 4th of August,” he says, “in the church of Our Lady of Perpetual Help. For the first time since its foundation, this community of 4,000 people has a priest.”

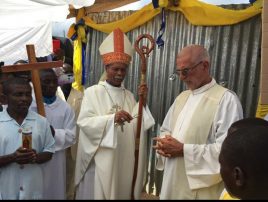

“Daily violence and the power of faith. The Wild West of a stateless country at the mercy of criminal gangs is almost inevitable. There is no way to protect the people, although there are high hopes for this UN mission requested by the Haitian government. But there is a deep faith and the strength of the mission can make a difference.

“The parish is a point of reference, the heart of everything: it is like living among the pioneers of the Wild West”,

where “everyday life was work, religion, open markets and fairs. But the people are modern and very active: there is an unimaginable dynamism.”

The bishops’ document. Faced with the daily scenes of death and devastation that have gripped the Caribbean country for years, the Haitian Bishops’ Conference wrote a heartfelt appeal last September. “What must we do as a Church and as a people to prevent armed gangs from killing us, from slaughtering us all?” the bishops wrote. Ten of them signed a document addressed “to the people of God, to men and women of good will”, admitting their helplessness. The daily terror in the capital, for example in Carrefour-Feuilles or Lilavois (to name but two of the districts controlled by the gangs) and the massacre in the Canaan area “seem to confirm that the gangs have been given free rein to attack the population”, the bishops denounced.

*editorial staff Popoli e Missione