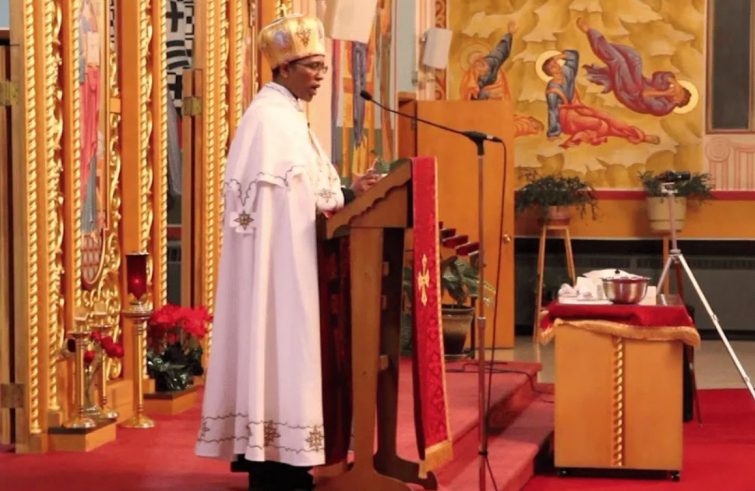

In Isaias Afewerki’s Eritrea, in power since 1993, repression of civil liberties and arbitrary imprisonment of dissidents (including their disappearance from the country) is virtually a daily occurrence. Thousands of people have been detained and have died in Eritrean prisons for years, including students, defectors, conscientious objectors and ex-heroes of independence. Now, however, the arrest of the Catholic bishop of Segheneity, Fikremariam Hagos, by security forces on October 15 at Asmara International Airport, is “worrying news”, Emilio Drudi, journalist and writer, author of essays on the Horn of Africa and migrations, such as ‘Una storia eritrea, Beyan, Adam, Amr’, told SIR.

Two priests were arrested together with Bishop Hagos: Abba Mihretab Stefanos, parish priest at St Michael’s church in Segheneity, and Abba Abraham a Capuchin Franciscan friar.

“The few who dare express dissent, albeit respecting the authorities in Eritrea, such as the Catholic Church or the Islamic school in Asmara, have been silenced,” said Drudi.

“But the most alarming fact is that this time the bishop was not placed under house arrest, but was brought directly to prison. It had never happened before.” The scholar recalled that “some time ago a priest died in custody, even though he was under house arrest. Not only the Catholics in Eritrea are being targeted: even the founder of the Islamic Church of Asmara who spoke out against the regime has been silenced.”

Two years ago Afewerki’s regime’s retaliation against Catholic Church facilities hit the headlines: 22 hospitals were shut down, their facilities seized by the State, patients were denied treatment. The same happened with 50 schools and 100 kindergartens run by the local Church. “They started by shutting down Church services and now they continue by silencing them,” says Siid Negash, an Eritrean diaspora activist in Italy, member of the Coordination for Democratic Eritrea (“Coordinamento Eritrea democratica”).

Two years ago Afewerki’s regime’s retaliation against Catholic Church facilities hit the headlines: 22 hospitals were shut down, their facilities seized by the State, patients were denied treatment. The same happened with 50 schools and 100 kindergartens run by the local Church. “They started by shutting down Church services and now they continue by silencing them,” says Siid Negash, an Eritrean diaspora activist in Italy, member of the Coordination for Democratic Eritrea (“Coordinamento Eritrea democratica”).

Tension runs high throughout the Country. “An entire nation is militarised and permanently at war with itself,” added Drudi. Compulsory military service is extended to all male citizens with no time limits. “The economy of war has impoverished Eritreans and reduced them to destitution,” Siid pointed out. “Rather than investing in education and production, the regime has been investing in war – and this is what keeps it going.”

The international community first learned about Afewerki’s atrocities on June 26 2015 with the release of the shocking 484-page “UN Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea”, alongside the accounts of witnesses, drawings of torture (widely circulated online) and analyses by experts from the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights.

The regime was accused of crimes against humanity.

Afewerki’s involvement in the ongoing conflict between forces under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and the TPLF-led separatist Tigray, “‘is an irrefutable truth'” denounced the members of the Democratic Eritrea Coordination. “The regime wants to wipe out the Tigray government,” they say.

“As far as I know, Bishop Fikremariam Hagos had only urged the faithful not to purchase goods seized from Tigray, the separatist region that has been subjected to a ruthless war for the past two years. And this speaks volumes about Asmara’s position with regard to Tigray,” Drudi added. “I believe that the peace treaty signed with Aby Ahmed’s Ethiopia in 2018 did not represent the beginning of a period of peace but of a military agreement – he said – which became a reality a year and a half later with the war declared on Tigray, backed and fought also by Afewerki.”

The UN periodically publishes reports on Eritrea. The latest one, dated 2017, is titled “Detailed findings of the commission of inquiry on human rights in Eritrea.”

The Eritrean government responded to the UN’s accusations by denying outright that any violation had been committed. “Eritrea is a secular nation – the government of Asmara wrote in a note – and religious freedom has statutory protections. The country has a rich history of religious tolerance and coexistence”.

“However, it is the government’s responsibility to ensure that tolerance and harmony are not disrupted by new developments: namely Islamic or Christian fundamentalism.”

And that is what is at stake here: considering the failure to conform to the regime’s violations as an expression of religious drift. “We honestly cannot understand on which grounds the government took the decision to shut down our hospitals,” said Father Mussie Zerai, an Eritrean priest and champion of his compatriots’ rights, some time ago. “Our hospitals used to treat two hundred thousand people every year, about 6% of the entire Eritrean population.”

(*) editorial staff ” Popoli e Missione “