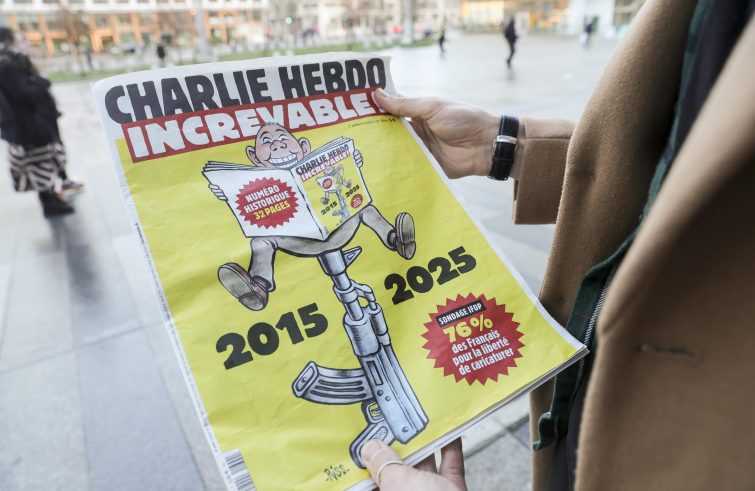

On 7 January 2015, two Islamist terrorists attacked the Paris office of the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo and gunned down 12 journalists with Kalashnikovs because, in their view, they had mocked Islam and the Prophet Muhammed and thus deserved to be killed. The 2001 attack was followed by several related terrorist attacks in Europe: Madrid in 2004, London in 2005 and Brussels in 2014. Other terror attacks ensued over the next decade: in Paris on 13 November 2015, in Nice and Berlin in 2016, in Brokstedt and Magdeburg in Germany in 2023 and 2024. The perpetrators of the Charlie Hebdo attack were tracked down and shot by police and army officers two days later. On 11 January 2015, millions of people marched through the streets of the French capital in defence of freedom of expression. A few days later, the survivors published a new issue of Charlie Hebdo, available in several languages and distributed in millions of copies worldwide, emphasising the fight against terrorism and the value of freedom of the press. “They didn’t kill Charlie Hebdo” is the key message of the 32-page special issue of the weekly, which will be available on newsstands across France for two weeks from Tuesday 7 January, exactly ten years after the massacre.

The attack on Charlie Hebdo “marked a turning point in jihadist terrorism in Europe and heralded the emergence of the escalating phenomenon of the Islamic State, with repercussions for international media and security – although it was not the Islamic State that claimed responsibility for the deadly attack on the French satirical magazine, but al-Qaeda in Yemen”,

Claudio Bertolotti, executive director of the Observatory on Radicalisation and Counter-Terrorism (ReaCT), which publishes the report on terrorism and radicalisation in Europe (https://www. osservatorioreact.it/), explained to SIR.

According to Bertolotti, while the attack “triggered a kind of competition between terrorist groups to claim credit and take control of the spread of ideological propaganda”, it was also “operationally relevant because it was the first terrorist attack in Europe that did not end with the massacre, but was marked by other events taking place at the same time”, Bertolotti said, referring to the terrorists’ attempts to flee and the simultaneous mobilisation of tens of thousands of security, defence and law enforcement forces. For the executive director of ReaCT ,

“It was the first high-intensity attack with a strong media and strategic impact.”

Could the attack on Charlie Hebdo be defined as an attack of a political nature, in view of its target and what it symbolised?

The attack was indeed politically motivated and it sent a clear message directed against a certain concept of freedom of expression, whether one agrees with it or not, which is unacceptable from a jihadist point of view. That attack was justified on ideological and religious grounds, enjoying broad consensus within Islamist groups and even among the more moderate Islamic fringes, which had previously expressed their condemnation of the cartoons of the Prophet.” This prompted a rallying call “to organise in great detail a military operation that was a far cry from today’s disorganised, copycat and often unsuccessful terrorist operations against very limited targets.” Ten years ago, the expert points out, “in Paris, the objective was clearly defined, there was no plan for martyrdom at the scene of the attack, but rather to continue fighting regardless of the initial attack. The terrorists’ aim was to strike and flee in order to be available for other possible future attacks. The two attackers had no intention of dying in combat. They became ‘martyrs’ after the response of the security forces.”

How has terrorism changed since 7 January 2015? You mentioned earlier that contemporary terrorism is a social phenomenon, unlike the terrorism that preceded it.

What we are talking about today is a social phenomenon on an individual basis. Compared to the Charlie Hebdo attack and the attacks of those years, with an organised platform of several actors involved in carrying out acts of terrorism, today’s terrorism has become an emulation phenomenon, a symbolic summoning of militant jihadism, of individuals of whose existence the terror groups’ headquarters know absolutely nothing except on the day of the attack, which they then tend to claim responsibility for if the attack is successful. These individuals are very difficult to track down because they act on external triggers, which could be an emotionally charged or media-hyped event, and because they are not integrated into an organisation that can be easily identified by security forces and intelligence services. Consider the victory of the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Gaza Strip, with Hamas’s call to strike Israel and its allies wherever they are, and Syria today, at a time when the Islamic State and Islamist groups already committed to jihadism rooted in the global jihadism of al-Qaeda stand in opposition to each other. These developments are likely to trigger the kind of disorganised, unsuccessful, one-man copycat attacks that characterise contemporary terrorism.

Should we interpret this shift from well-organised, ramified terrorism to disorganised emulations of terrorism as a failure or as a progress of the phenomenon of terrorism?

Unfortunately, I think it is a success, based on the adaptability of terrorism. When the Islamic State was formed in 2014, the then spokesman of the Islamic State of Syria and Iraq called on the Islamic ummah to strike everywhere on an individual basis. And that became the terrorist modus operandi.

Potential terrorists know that if they succeed, they will be recognised as ‘soldiers’ and ‘martyrs’, and that is enough for them. With the emulation factor, anyone can see themselves as a bearer of the intentions and ideals of the Islamic State.

What counter-terrorism strategies were adopted after the Charlie Hebdo attack and which new ones should be implemented today in the face of such emulated terrorist attacks?

The Charlie Hebdo attack led to a comprehensive reassessment of the organisation and legislation of counter-terrorism from a legislative and operational point of view. In 2015, although limited to the operational phase, Europe exerted great pressure on individual states to adopt very strict legislative measures in the field of counter-terrorism and prevention. France, Italy, Germany and the United Kingdom all developed highly effective legislative tools.

The Dambruoso, Manciulli draft law on “Measures for the prevention of radicalisation and jihadist extremism” has been on the table in Italy for two legislatures, the current one would be the third. Could it be a useful tool for the promotion of social prevention measures?

The bill could have been a useful tool for the promotion of social prevention in order to counteract the incipient radicalisation and adherence to the ideological paradigm of terrorism. In fact, the bill envisages the cooperation of social services, the police, educational institutions and the Ministry of Education in order to prevent at an early stage, especially during the adolescent years, young people from adhering to this “model” of violence. This bill was subsequently endorsed by MEPs Emanuele Fiano and Matteo Perego di Cremnago. They extended the measures to include right-wing and left-wing extremism. Today, the bill needs to be updated in light of the changes that have occurred over the last 10 years with regard to the phenomenon of terrorism. Italy currently lacks a prevention instrument.