“By going to Kyiv, we are saying that we are all Ukrainians and that we are all Europeans. We are here with you and we will be there in person to make it clear to you, even at personal risks.” That is “pacifism” as explained by Riccardo Bonacina, editor-in-chief of the Italian weekly Vita and among the promoters of Project MEAN (European Movement of Nonviolent Action), and of the march for peace to be held in Kyiv on Monday July 11, with 150 people taking part in the event. “There cannot be more of us for security reasons,” he explains. Nevertheless, the initiative is open to all and on the evening of Sunday, July 10, the day before the demonstration, fifteen public squares in Italy and Europe (including one in London) will be connected to Kyiv, where an additional 500 activists will make their voices heard and express their support for Ukrainian civil society. On Monday 11, participants in Kyiv will attend a general assembly during which the mayor and deputy mayor of the city, and the apostolic nuncio, will take the floor. Thirty-five Italian organisations support the initiative, among them Catholic Action. “This initiative was conceived a few days after the outbreak of the war”, says Bonacina. Meetings with representatives of civil society were held over the past months, including in Ukraine with a view to understanding the situation, forging relations, and promoting initiatives. It was a great challenge”, the journalist tells us.

And how did it go?

And how did it go?

At first, when we spoke of peace and of the need to break away from the logic of war, we were told: “bring us weapons and help us protect our people who are fleeing.” Over the course of the past two months, a different understanding emerged to the effect that non-violence is a weapon of a different kind, a weapon of ‘mass construction’. We engaged in dialogue and in June we met with numerous Ukrainian organisations and with the municipal authorities of the city of Kyiv. We are going there without judging what they are doing. On the contrary, we understand it, but the idea is to work for peace understood as another form of resistance and to jointly envisage a future marked not by armed opposition.

We chose this date, July 11, as it is the feast day of St Benedict, Patron Saint of Europe, but it also marks the day of the massacre of Srebrenica, the biggest massacre since the end of World War II, when 8,000 Muslim youths and men were massacred in the presence of the UN. July 11 is therefore a day of hope as well as the day of a historic debacle of our recent past.

The war in Ukraine will not be resolved any time soon. It is bound to be long and painful. Are there any concrete prospects for the notion of ‘non-violence’ that you will bring to the heart of Ukraine?

For one thing, war invariably fuels the binary friend/foe, good/bad, weapons/non-weapons approach, and it gradually shapes a world with no room for understanding, in fact it increases hatred even amongst family members. We felt it was important to send a sign in order to step out of this logic via thoughts and relationships whereby agreement is at least foreseeable. They are weary of war.

Admittedly, this is not a war that will reach a ceasefire any time soon. But if we want to look to the future, we must try to follow a different rationale, and work together to identify an alternative course of action.

In addition to the friend/foe binary pattern, in Ukraine there is another dramatic one, that of attacked/aggressor. Faced with this reality, how can non-violence be expressed in concrete terms?

By embracing those who were attacked, helping them, supporting them, coming to their rescue. But it can also be concretely expressed by initiating approaches that may be somewhat different and transcend armed resistance. We are not ideological peace activists. In the last few days we have been described as ‘concrete pacifists’ and ‘peacemakers’. The latter description resonates with us. It is our aim.

Ukraine is not a stage for neither our arguments or our feelings. We are not going to Ukraine to say that we are good and peace-loving persons. We are going there to embrace the Ukrainian people and to help them.

You met with Ukrainian associations. What are their requests, and their greatest needs?

They want to feel that they actually belong to Europe.

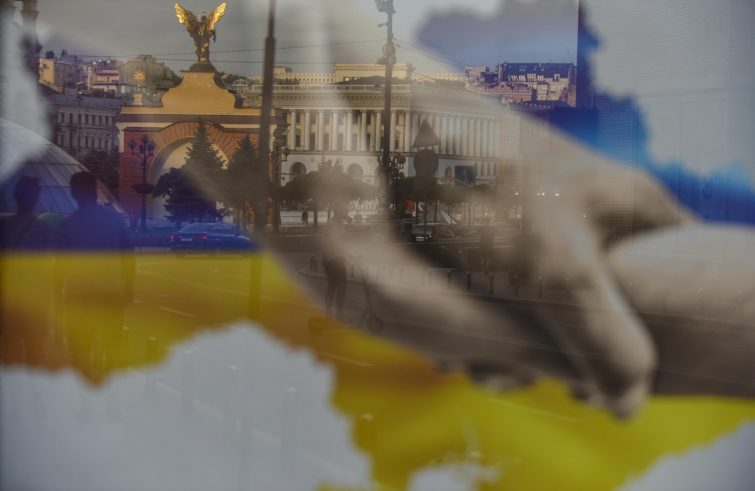

Therefore, they need Europeans to go there. Our idea is to show them that the pro-Europe project they initiated at Maidan Square in 2014 is not simply an issue opened and closed in Ukraine and within the European institutions, but that it pertains to civil society and it involves us all.

Why not promote a march in Moscow?

Next Friday evening, a group of Russians from the “Free Russians Community” association will hold a demonstration against the war and against Putinism in Milan’s Duomo Square at 7.30 p.m. This is one important sign. We have been trying to establish a dialogue with Russian civil society as well, but it’s not easy. A great physicist was arrested a few days ago. His life was coming to an end in the intensive care unit of a Novosibirsk clinic. They put him in jail. He died the next day. They went from an authoritarian regime to a totalitarian regime. It’s complicated.