Their eyes filled with tears, their faces strained, their hands are shaking. While visibly worn out and exhausted, they are eager to talk about what they have seen, and hold back the tears. They want to be strong. They are the women of Ukraine. They hold their children with one hand and wipe away their tears with the other, in order not to be seen crying. We are at the St Charles Borromeo seminary in Kosice, eastern Slovakia, the second most populated city in the country, on the border with Ukraine. Father Andrea Kacmar, vice-rector of the seminary, said that priests and seminarians have reserved a section of the facility for women fleeing the war: some fifty of them are presently housed there, along with 24 children. Kseniya, 38, is one of them. She left Uzhgofod with her three children.

Their eyes filled with tears, their faces strained, their hands are shaking. While visibly worn out and exhausted, they are eager to talk about what they have seen, and hold back the tears. They want to be strong. They are the women of Ukraine. They hold their children with one hand and wipe away their tears with the other, in order not to be seen crying. We are at the St Charles Borromeo seminary in Kosice, eastern Slovakia, the second most populated city in the country, on the border with Ukraine. Father Andrea Kacmar, vice-rector of the seminary, said that priests and seminarians have reserved a section of the facility for women fleeing the war: some fifty of them are presently housed there, along with 24 children. Kseniya, 38, is one of them. She left Uzhgofod with her three children. In their stories there is always a before and an after. Kseniya used to work as an attorney. She speaks fluent English. She used to lead a very normal life. But when the heavy shelling began, they were forced to take refuge in underground shelters ever more frequently, until she and her husband realised it was best to leave the city and head somewhere safer. She left alone by car with her three children, stopped in Hungary, then fled to Slovakia. Kseniya says what impressed her the most upon their arrival at the major seminary in Kosice, where they were welcomed, was the silence and the ordinary noises of everyday life. But her children keep asking her: “When are we going back home?.” Angelica fled from Bucha, a town near Kiev that has been viciously hit by Russian shelling. Her account is a confused and hurting description of the fighting she saw in the sky and on the ground. Helicopters. Ukrainian anti-aircraft. Bombings. “People have been killed”, she says. When the mayor urged residents to leave the city, she and her three-year-old niece got into the car and drove away. She escaped with what she had with her. The husbands have remained and are now fighting in the local defence divisions. “The soldiers storm into houses and destroy everything. There is no more water or electricity. It took me five days to get out of Ukraine. It will probably be impossible to ever return, we have nowhere to go.” She stops. She lifts her gaze and says: “We used to lead a normal life. We had everything. Now we have nothing. That’s what it means to be refugees. It’s terrible.”

In their stories there is always a before and an after. Kseniya used to work as an attorney. She speaks fluent English. She used to lead a very normal life. But when the heavy shelling began, they were forced to take refuge in underground shelters ever more frequently, until she and her husband realised it was best to leave the city and head somewhere safer. She left alone by car with her three children, stopped in Hungary, then fled to Slovakia. Kseniya says what impressed her the most upon their arrival at the major seminary in Kosice, where they were welcomed, was the silence and the ordinary noises of everyday life. But her children keep asking her: “When are we going back home?.” Angelica fled from Bucha, a town near Kiev that has been viciously hit by Russian shelling. Her account is a confused and hurting description of the fighting she saw in the sky and on the ground. Helicopters. Ukrainian anti-aircraft. Bombings. “People have been killed”, she says. When the mayor urged residents to leave the city, she and her three-year-old niece got into the car and drove away. She escaped with what she had with her. The husbands have remained and are now fighting in the local defence divisions. “The soldiers storm into houses and destroy everything. There is no more water or electricity. It took me five days to get out of Ukraine. It will probably be impossible to ever return, we have nowhere to go.” She stops. She lifts her gaze and says: “We used to lead a normal life. We had everything. Now we have nothing. That’s what it means to be refugees. It’s terrible.”

- (Foto Sir)

- (Foto Sir)

- (Foto Sir)

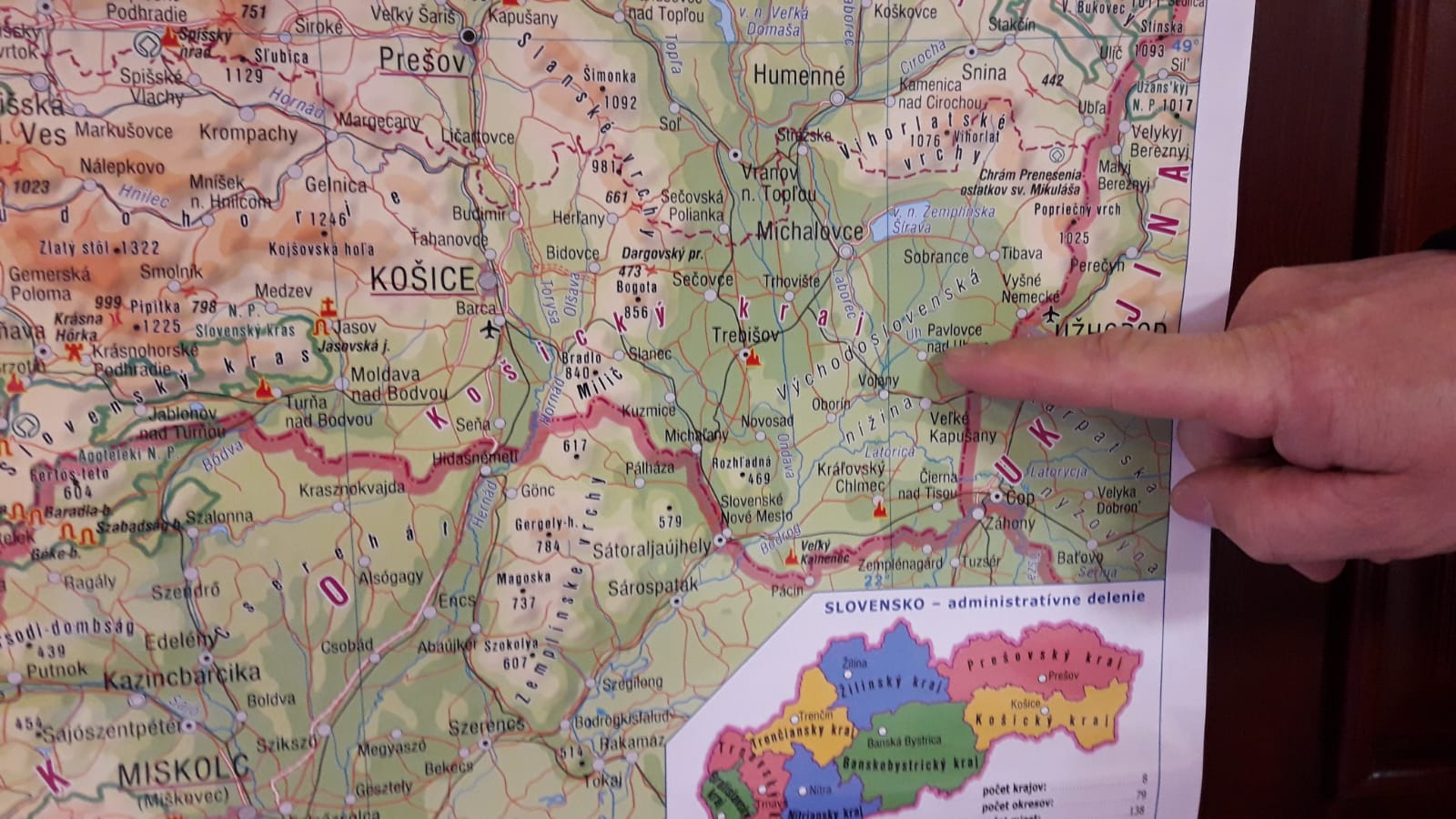

Kseniya and Angelica’s stories are intertwined with those of many others at Vysne Nemecke, on the Slovakia-Ukraine border. A slow yet continuous stream of people pour out of the customs checkpoints. Almost all of them are women and children. There are some elderly people, most of them alone. They arrive with just a few bags. Pushchairs and dogs on a leash. They are received by soldiers and volunteers representing the Red Cross, Caritas, the local Catholic Church and the Order of Malta. Further on, shuttles bring them to the Michalovce hotspot where the necessary documents for temporary refugee status and health care can be obtained.

Kseniya and Angelica’s stories are intertwined with those of many others at Vysne Nemecke, on the Slovakia-Ukraine border. A slow yet continuous stream of people pour out of the customs checkpoints. Almost all of them are women and children. There are some elderly people, most of them alone. They arrive with just a few bags. Pushchairs and dogs on a leash. They are received by soldiers and volunteers representing the Red Cross, Caritas, the local Catholic Church and the Order of Malta. Further on, shuttles bring them to the Michalovce hotspot where the necessary documents for temporary refugee status and health care can be obtained. The whole process is conducted in an orderly and polite manner. Shuttles are loading and unloading non-stop. But the hearts are broken, and a surreal silence prevails. “In the first days of the conflict, the situation was nothing like this. It was much more chaotic,” we are told by Miroslav Gieci, on-duty coordinator of the Order of Malta’s volunteer workers. They were among the first to offer assistance, bringing warm beverages, food for adults and for children. People were arriving after a three- to four-day journey, often without eating or drinking. Many of them, including children, were found in a state of dehydration. However, the volunteers immediately became aware of the presence of looters and thieves in the area.

The whole process is conducted in an orderly and polite manner. Shuttles are loading and unloading non-stop. But the hearts are broken, and a surreal silence prevails. “In the first days of the conflict, the situation was nothing like this. It was much more chaotic,” we are told by Miroslav Gieci, on-duty coordinator of the Order of Malta’s volunteer workers. They were among the first to offer assistance, bringing warm beverages, food for adults and for children. People were arriving after a three- to four-day journey, often without eating or drinking. Many of them, including children, were found in a state of dehydration. However, the volunteers immediately became aware of the presence of looters and thieves in the area.

“I would go home and couldn’t sleep at the thought that someone might break into the wrong car,” says Miroslav, who works as a book seller. The whole area is now under surveillance. The police are making extensive cross-checks and the Italian financial police have also been deployed on site.

“I would go home and couldn’t sleep at the thought that someone might break into the wrong car,” says Miroslav, who works as a book seller. The whole area is now under surveillance. The police are making extensive cross-checks and the Italian financial police have also been deployed on site.

Every church facility here in Kosice is involved in humanitarian relief efforts. The latest figures show that the archdiocese has provided short or longer-term accommodation and meals for 2,550 people from Ukraine. When the war broke out, it was immediately clear to Anna Kolesavora at the Domcek in Vysoká nad Uhom that Ukrainians would be fleeing their country and that thousands would be arriving here too.

Every church facility here in Kosice is involved in humanitarian relief efforts. The latest figures show that the archdiocese has provided short or longer-term accommodation and meals for 2,550 people from Ukraine. When the war broke out, it was immediately clear to Anna Kolesavora at the Domcek in Vysoká nad Uhom that Ukrainians would be fleeing their country and that thousands would be arriving here too. Domcek is a four-house facility, all of the housing units have been renovated and furnished. The centre hosts every year five to eight thousand young people who arrive for spiritual exercises and meetings. Some stay for a year of voluntary work. A meeting on synodality was taking place when the news from Ukraine reached alarming levels.

Domcek is a four-house facility, all of the housing units have been renovated and furnished. The centre hosts every year five to eight thousand young people who arrive for spiritual exercises and meetings. Some stay for a year of voluntary work. A meeting on synodality was taking place when the news from Ukraine reached alarming levels.

“We decided to put everything else on hold and started preparing for accommodation immediately,” says Fr Pavol Hudak. “We contacted the mayor and proceeded to clean the structure and look for beds. That night, everything was in place, and we welcomed the first 38 children and their mothers. A total of over 400 people have stayed here. Now the facility is home to the volunteer workers who offer their help at the border. The women are very tired when they arrive. They only ask to be given a place to sleep and something to eat. They have been driving for long distances and are disoriented. For this reason, maps can be found everywhere in the compound, so the volunteers can show them where they are and which route to take to continue their journey. “We have seen mothers pushing a baby carriage with one hand and holding their child with the other,” says the priest. “We have seen husbands drive back and women weeping for hours in their rooms.” But the call of life was greater than surrender, stronger than tears. A mother with two children told us: “when we were hiding in the shelters, without food and water, we realised we would rather risk our lives and get out than starve in the underground shelters.” Those are the women of Ukraine, they hold back their tears but never stop fighting.

“We decided to put everything else on hold and started preparing for accommodation immediately,” says Fr Pavol Hudak. “We contacted the mayor and proceeded to clean the structure and look for beds. That night, everything was in place, and we welcomed the first 38 children and their mothers. A total of over 400 people have stayed here. Now the facility is home to the volunteer workers who offer their help at the border. The women are very tired when they arrive. They only ask to be given a place to sleep and something to eat. They have been driving for long distances and are disoriented. For this reason, maps can be found everywhere in the compound, so the volunteers can show them where they are and which route to take to continue their journey. “We have seen mothers pushing a baby carriage with one hand and holding their child with the other,” says the priest. “We have seen husbands drive back and women weeping for hours in their rooms.” But the call of life was greater than surrender, stronger than tears. A mother with two children told us: “when we were hiding in the shelters, without food and water, we realised we would rather risk our lives and get out than starve in the underground shelters.” Those are the women of Ukraine, they hold back their tears but never stop fighting.

- (Foto Sir)

- Foto Conferenza episcopale slovacca

- Foto Conferenza episcopale slovacca