Brent Renaud, 50, American photographer and video-maker, was killed in a barrage of bullets while driving with a fellow American journalist and a Ukrainian driver through the streets of Irpin, not far from Kyiv. He was documenting the flight of refugees from yet another martyred city, shattered by the fury of the invading Russian army.

Renaud – who used to work alongside his elder brother Craig – had chronicled numerous armed conflicts and disasters throughout the globe -whether man-made or natural. The news of his death was met with ominous words of retaliation from Washington.

Sadly, his death is not an isolated incident.

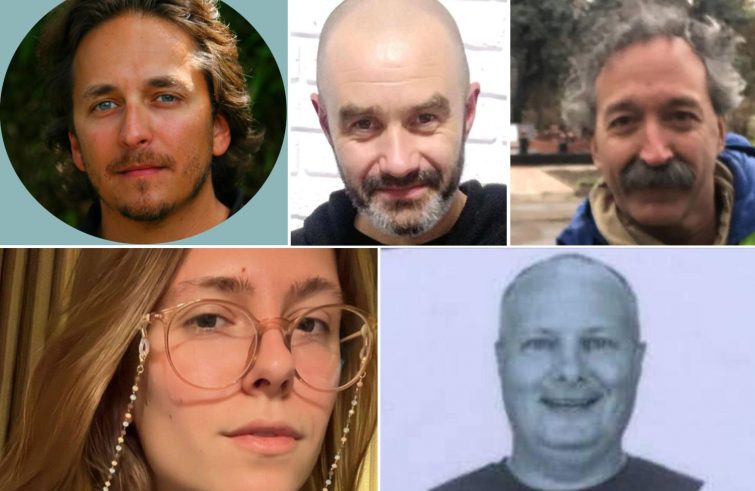

New names have been added to the list of victims wearing “press” badges, and the numbers might increase further. At present, five people have been killed while reporting on the rampaging Russian invasion of Ukraine. These include, in addition to Renaud, Benjamin Hall, Pierre Zakrzewski, Alexandra Kuvshinova and cameraman Yevhen Sakun. Ukrainian sources estimate that some forty reporters have been wounded. While Russian-Ukrainian journalist Marina Ovsyanikova, who had protested on live TV against the war is being prosecuted for expressing her anti-war convictions.

But just how much is the life of a journalist worth?

It is worth just as much as the lives of the countless Ukrainian civilians – men, women, old people and children – who have lost their lives in the Russian invasion. It is worth as much as the life of a child, a woman, a man shot by a rifle, a bomb shrapnel, or killed in a collapsing building. It is worth as much as the life of a Ukrainian soldier fighting to defend his country. It is worth as much as the life of the Russian soldier who was sent to die for a wrong cause on Ukrainian soil.

They are all victims of the same murderous rage, of a murderous policy that aims to settle problems with weapons rather than with dialogue and diplomacy.

Perhaps the only – albeit not insignificant – difference lies in the fact that we know the names of journalists killed on the ground. News outlets readily recount their personal and professional stories, and rightly so. But we shall never know the names of others who have died today, yesterday or tomorrow in this new, disastrous war, nor their tragically destroyed lives or their broken dreams. We will never know the faces of the children killed in Mariupol, the women raped by Putin’s soldiers, the old men who died of a heart attack from the terror caused by the missiles fired on Kiev and on other cities in Ukraine.

Likewise, we know very little – nor do news outlets make any effort to inform us – about the names and the lives of the victims of dozens of armed conflicts ongoing in the world today:

in Africa, in the Middle East, in Latin America. Those wars are unknown to us, yet they are just as real, just as tragic and incomprehensible. Wars that we are ostensibly unaffected by, only to discover that the tragedies and instabilities they create will have political, social, migratory, economic and energy repercussions that will sooner or later affect our own, all too often uncaring, regions. In his book “Tu non uccidere” (“Thou shalt not kill”), published in 1955 at the height of the Cold War, Don Primo Mazzolari (1890-1959), a pacifist parish priest based in the Po Valley, on the frontline in World War I, wrote: “There is no place for war – both from a Christian and logical standpoint. In Christian terms, because God has commanded: ‘Thou shalt not kill’ (and ‘Thou shalt not kill’, however much one may argue about it, means: “Thou shalt not kill”); in addition, [at war] brothers are killed, children of God, redeemed by the blood of Christ. Killing a man is indeed homicide, because a man is killed; it is suicide because it devours the social body, including the mystical body, which the slaughterer himself shares. At the same time it is deicide, because with a sort of “execution in effigy” it assassinates the image and likeness of God, reflected in the blood of Christ, whereby, through grace, we share in the divinity of Christ.”

A vocabulary marked by the passing of time, and yet extremely relevant today.

*Director-General, Missio Foundation