(from Jerusalem) Ilia snuggles up to Father Ibrahim’s habit and smiles, almost hiding herself from view. The unexpected visit of a small ‘Diomira Travel’ group from Italy – 9 priests from the diocese of Piacenza, Milan and Cremona – surprised everyone at the Terra Sancta School in Jerusalem.

Since 7 October, the day of Hamas’ terror attack on Israel and the ensuing outbreak of war in Gaza, Ilia has been repeatedly asking her teacher if she could make a phone call to her father to find out where he is. She fears losing him to the bombs and rockets. Ilia’s fears are echoed by many other Palestinian children afflicted – like their Israeli counterparts – by the Gaza war. Father Ibrahim Faltas, Vicar of the Holy Land Custody, tells Ilia’s story as he greets the school’s 400 students who resumed classes on Monday 8 January after the Christmas break. “Returning to school,” he explains, “is a way of recovering a glimpse of normality, trust and serenity. Everything here is a reminder of the war, hatred, resentment and, above all, fear. Just before Christmas, we held a demonstration calling for an end to the war and a resumption of dialogue. We firmly believe that dialogue is the way out of this tragic situation.

While others wage war, we are builders of peace.

The Jews are afraid, the Israeli Arabs are afraid, the Palestinians are afraid. Everybody fears their fellow others. Arab and Israeli co-workers who used to be on good terms at the workplace are no longer on speaking terms. It will take years to heal Israeli society at its core. But it must be done.”

Escalating crisis. Ilia’s fears extend to the many families who have lost their jobs. Tourism and pilgrimages, a major source of income, have virtually collapsed with the outbreak of war. As a result, there are no tourists or pilgrims to be seen in the holy places, and Jerusalem and Bethlehem are almost deserted. The only visitors to the Holy City are a few groups of Indonesians and groups from the Horn of Africa who travelled through Jordan and Egypt. In hotels across Israel, the tourists and pilgrims have been replaced by thousands of displaced Israelis who were living in areas along the borders with Gaza and Lebanon before the war, at the gunpoint of Hamas and Hezbollah. The situation is even worse for the over ninety Palestinian hotels in Bethlehem, all of which are virtually closed. The birthplace of Jesus is de facto sealed off. Checkpoints are only open for a few hours a day, allowing access only to holders of special permits issued by Israel. In the meantime, some 70,000 Palestinians who used to cross the Israeli checkpoints on a daily basis from the West Bank to enter Israel to work have seen their permits suspended or revoked. They are now unemployed. The economic crisis is increasingly intertwined with the military crisis, with tragic social consequences.

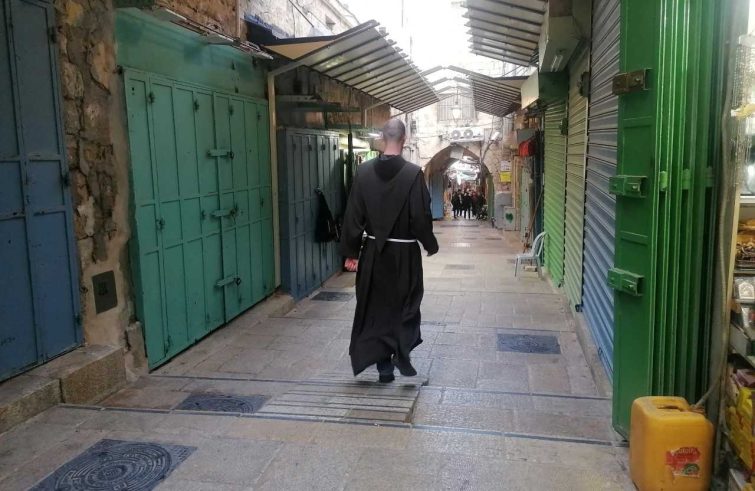

Empty shrines. From the Convent of the Palms of Bethphage, on the eastern slope of the Mount of Olives, past the Carmelite Convent of the Pater Noster, the Dominus Flevit shrine, all the way to Gethsemane, it is hard to meet anyone who is not a resident. Even to enter the shrines, you have to knock on the door to be let in.

Empty shrines. From the Convent of the Palms of Bethphage, on the eastern slope of the Mount of Olives, past the Carmelite Convent of the Pater Noster, the Dominus Flevit shrine, all the way to Gethsemane, it is hard to meet anyone who is not a resident. Even to enter the shrines, you have to knock on the door to be let in.

“When I realised that someone had rung the bell, I was surprised!”, says Brother Silvio, the custodian of the shrine, with a smile. “No one has entered this place since 7 October.”

In spite of everything, the Franciscans remain committed to their mission of serving the poorest, not only Christians, because, as the friar explains, “this is the best way to respond to war and to violence.” The street below the Basilica of the Agony, also known as the Church of all Nations, is completely empty. The usual rows of buses waiting to pick up groups of pilgrims are gone, so the journey to the Holy Sepulchre in the heart of Jerusalem’s Old City is not a long one. There are no pilgrims, only workers and archaeologists from Rome’s La Sapienza University engaged in archaeological excavations inside the basilica, known to local Christians as the Church of the Resurrection. Almost all the shops near the Holy Sepulchre have their shutters down. “Those that are open,” says a souvenir shop owner on Saint Helena Road, a few dozen metres from the Basilica, “do so only to pass the time and in the hope of earning a living. We had bounced back after the Covid pandemic, but now it’s hard.”