Ultimately the pandemic hit low-income districts and Argentina’s so-called villas miseria, (misery villages), where a considerable segment of the urban population of Buenos Aires and its boundless suburbs live. A dreaded – and to a large extent anticipated – development. In the last few days, the number of infections has reached the exponential trend seen at other latitudes. It should come as no surprise. The priests living in the villas had warned it could happen.

Covid-19 containment measures imposed by government authorities for the capital city are not enforceable in places where thousands of people live in tiny dwellings, where life is mostly lived on the streets, where health care facilities are virtually non-existent.

They therefore acted accordingly, promoting practical solutions for the inhabitants of low-income neighbourhoods, with the watchword “Stay at home, stay in your neighbourhood”, adopted by the President of Argentina and reiterated by him at national level. Hence as the plague, as it is called in the villas, crossed the borders of these pockets of deprivation during the past few days, spreading into the most densely populated areas,

efforts were intensified to prevent it all from burning down like a fire in a haystack.

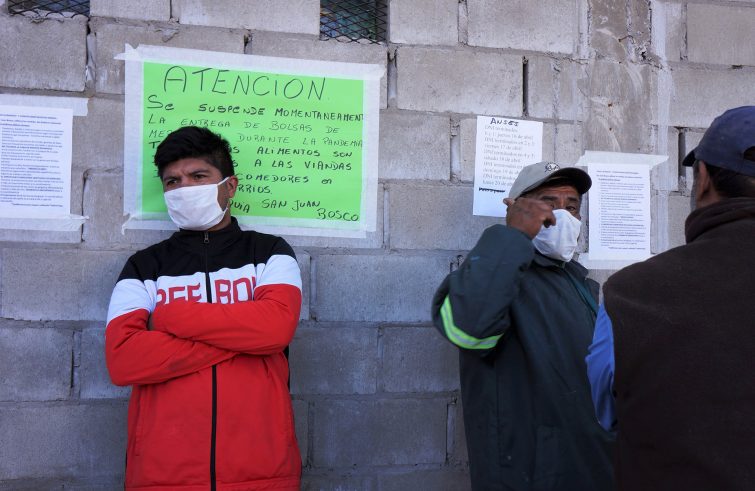

The number of residential homes for the elderly, those for the homeless, the Hogar treatment centres for drug addicts, all of which are high-risk groups, are being increased. People standing on line for food parcels in front of the many soup kitchens set up in the villas are also increasing, since all normal activities of Argentina’s cartoneros have closed, and those who lived off the selling of recyclables can no longer roam the streets seeking items to sell. Waste recyclers no longer lug their carts rummaging through the most promising piles of rubbish as they did every morning until a few days ago. Even those who used to make a living as handymen, cutting the lawn of someone’s garden, repainting a gate or a front wall, emptying a basement, working as daily move helpers, are no longer in demand. The street vendors that used to crowd the villa have parked their coloured tin trucks, the women frying potatoes and cornbread in street corners have turned off the stove. Manual labourers, many of them from Paraguay, spend whole days twiddling their thumbs.

The number of residential homes for the elderly, those for the homeless, the Hogar treatment centres for drug addicts, all of which are high-risk groups, are being increased. People standing on line for food parcels in front of the many soup kitchens set up in the villas are also increasing, since all normal activities of Argentina’s cartoneros have closed, and those who lived off the selling of recyclables can no longer roam the streets seeking items to sell. Waste recyclers no longer lug their carts rummaging through the most promising piles of rubbish as they did every morning until a few days ago. Even those who used to make a living as handymen, cutting the lawn of someone’s garden, repainting a gate or a front wall, emptying a basement, working as daily move helpers, are no longer in demand. The street vendors that used to crowd the villa have parked their coloured tin trucks, the women frying potatoes and cornbread in street corners have turned off the stove. Manual labourers, many of them from Paraguay, spend whole days twiddling their thumbs.

The informal economy, as it is usually termed, is at a standstill. The small trade activities that sustained the population of the villa is virtually halted.

There is an aspect underlying this emergency that deserves to be noted, which could have positive repercussions in the near future. A friend who frequents the villa where I live noticed that, among the many changes characterising this time of lockdown, unprecedented in modern history and not only in Argentina, there is a “transformation” which, according to him, represents a novelty also with regard to politics, due to have positive repercussions on the exercise of age-old authority.

There is an aspect underlying this emergency that deserves to be noted, which could have positive repercussions in the near future. A friend who frequents the villa where I live noticed that, among the many changes characterising this time of lockdown, unprecedented in modern history and not only in Argentina, there is a “transformation” which, according to him, represents a novelty also with regard to politics, due to have positive repercussions on the exercise of age-old authority.

Power – he remarked as we returned from one of the many trips to the province to collect food donations – for the first time tends to coincide with authority.

This is how he explained his observation.

Before the lockdown was imposed in the villas, efforts were being made against the abortion bill that the Argentine President and his government intended to propose to the nation’s legislative body after its defeat last year. The underlying argument was that it was a public health measure that a legitimately formed government is required to pass so as to ensure the safety of women victims of illegal abortions. Now that this same government is facing a situation that dramatically affects public health in all respects, in order to reach out to the most socially marginalised groups – that in fact reported the highest number of infections – it is turning to those who understand them deeply, namely the so-called curas villeros, the priests serving the villas, dear to the Argentinean Pope. Hence power assumes the authority they have among the poorest to impose containment measures in suburban, low-income settings where it would otherwise not be heard.

What happened? – this friend wondered. The opposite of when politics is not firmly grounded in reality, which it does not know and thus cannot govern.

Power takes on the perspective of those serving the underprivileged, in this case the curas of the villas, in order to assume the authority they have in the shantytowns and be heard.

This is a positive transformation that is likely to teach a lesson to those in power even in the near future.

I wish to add, confirming this point, a corresponding thought of Pope Francis expressed in an interview on Latin America a few months ago: “Sometimes, politicians in the various organizations seeking to help the poor, struggle to understand the cultural traits of these poor people. This is why their help will always be perceived as ‘external’ to them, as something coming from well-meaning but odd people. Such aid will certainly bring relief, but it will not have the power of transformation, of consolation, of inspiration, of true closeness.” He continued: “In the case of priests living in very poor districts attempting to sustain people according to their specific circumstances and inherent cultural traditions, what happens is different. The local residents perceive them as members of their community: they live with them, they share their limitations, their insecurities, their fears, their dreams.

I wish to add, confirming this point, a corresponding thought of Pope Francis expressed in an interview on Latin America a few months ago: “Sometimes, politicians in the various organizations seeking to help the poor, struggle to understand the cultural traits of these poor people. This is why their help will always be perceived as ‘external’ to them, as something coming from well-meaning but odd people. Such aid will certainly bring relief, but it will not have the power of transformation, of consolation, of inspiration, of true closeness.” He continued: “In the case of priests living in very poor districts attempting to sustain people according to their specific circumstances and inherent cultural traditions, what happens is different. The local residents perceive them as members of their community: they live with them, they share their limitations, their insecurities, their fears, their dreams.

Social agencies wishing to serve the poor and ‘with the poor’ could find in these priests their best allies. They would help them understand who these people are, how they are and how they can truly be supported from within and from grassroots level

(…)There can be no real and lasting change unless it arises ‘from within and from below'”. [Pope Francis. Latin America. Conversations with Hernán Reyes Alcaide. Edizioni San Paolo, 2019].